Friday, 8 May 2009

Getting out there!

Otto Dettmer

Otto Dettmer

Otto studied at Kingston University. He has always had an edge for screenprinting within his work and in 1995 at Kingston, it came about for him.

Dettmer, is very fond of producing a lot of self promotion- Mail-outs for clients for example. His work is very stripped back, and he consistently uses a limited colour palette. His work communicates effectively and is very simple.

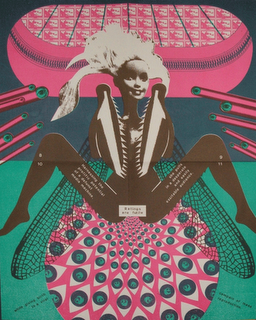

His influences range from Saul bass, to Rodchenko ad el Lissitsky, the renaissance and figures have had a compulsivee impact upon his work presently whch he was kind enough to show us whilst he gave a talk at Stockport College. A very fururistic look, a little more empahsis on design and not as simple as some of his work but still very effective.

He began self promotion as soon as he left college, he knew of its importance, that being the reason he is still overemphasising on it today, the same as any other illustrator. But the market more recently has become very competative so there is more reason to be. He would visit London as often as he could a week and produced a range of editorials for european magazines. Otto has a very large range of stock illustration on his website – some of his past works or spot elements from illustration, expired licence which have been resold for half price. He come across very business like. When giving his talk, Otto stated the importance of being on the internet and making yourself visible to clients. He also began to talk of the future illustration being quite moving image or animation- his futuristic work depicts a feel of this. The pieces have been created using photographic reference of figures, insects and shapes, depicting a chaging monster in the city.

TOO many design graduates-essay

Every year, education establishments produce thousands of illustrators, but what happens to them all after they graduate? after reading relevant articles and asking exgraduates of the situation, I believe self-promotion and the initiative of the illustrator plays a big role in the establishment of a designer. Not only that though, the industry cannot commission every illustrator after graduation. There are not possibly enough magazines, newspapers and book jackets available. Darrell Rees stated this fact within his book – How to be an Illustrator. I also believe it to be attributable that there is an expansion of practises that come under illustration- animation for example. But then this would clash with multimedia design. You will also notice that most illustrations recently, are quite dependant upon graphical shapes and elements produced and rendered entirely on the computer. This could also suggest a shift into graphic design. It seems illustration holds the means of design in any field. So what has been happening when these students graduate? Well, it has become apparent that photography, especially manipulated photography has become 'more effective in comparison to an illustration as Steven Heller states in an interview, that, "I am an advocate of illustration and saddened by its loss of stature among editors who feel photography is somehow more effective (and controllable)." Manipulated photography, because of the reality, the image says everything it can, in as truthful an opinion as possible and so in some opinions it is more substantial.” Yet, I don't just believe this to be the only means to have had impact of the loss of illustration graduates within the design industry. I believe it more to be the the fault of the illustrator themselves. If your work is original and demonstrates strong concepts, then your illustration is doing its job. But how do you let people know that your work is what they are looking for?

To begin with, making contacts becomes an important part of self promotion. At first, just getting your work seen, to gather opinions on it, but then to do your market research on what sort of mixtures are being produced within the industry and not adapting yourself but presenting yourself to be what a client needs.

I read within an issue of Varoom, that 'the most fundamental part of self promotion is letting the work speak for itself'. Which inevitably leads down to communication skills and getting the message across to the viewer instantly. Your ideas become apparent straight away, yet, it doesnt necessarily become an act of printing out as many posters as possible, you have to target the right people.

Every illustrator wants to be noticed, and every commissioner/client wants new talent, original work and thinking. Yet to be noticed you need to work at it, you need to be progressive and proactive. This approach to self-promotion has become the establishment of any successful practitioner. But, once you have inspired people with your work, you cannot wait for the phone to ring. Using your skills as a visual communicator, you have to inspire people. You must arrange meetings, send out mail shots, postcards and keep at it.

After reading apparent articles on self-promotion, the majority speak of how commissioners find their illustrators. This is where self promotion becomes important, targeting the right people. Obviously a newspaper is seen and read everyday. Everyday an illustration is illuminated and more often than not a commissioner will see your work. 95% of the time, the internet is maybe the biggest chance of finding new talent and issues in comparison to a physical portfolio.There are also many competitions about for illustrators to enter into where new talent would be noticed and also internships with Agencys. internships provide opportunities for students to gain experience in their field, determine if they have an interest in a particular career, and it is a big chance to create a network of contacts.

As I have been questioning exgraduates, some who have progressed within the illustration industry, others who have had some drawbacks, I specifically began to question their opinion on the following question

“what makes the difference between success and failure when trying to establish yourself in the design industry?

I received numerous returns to the question, most picking up on the valuable point of self promotion and the gathering of new contacts. 'Raw talent is important and should be the deciding factor that separates a commercially successful illustrator from a respected one. To develop a long term career it is important to develop your own approach to your own work and to keep it fresh and stimulating to yourself. Avoid getting jaded and continue to follow the professional approach listed above and you have a real chance of making it long term.' as andy pavitt states. Ben Jones who is based in London but is presently working, back in Manchester, stressed his views on the importance of developing a number of illustrations a day, and not just when you are a assigned a brief.'Art directors need to see your work before they can commission you.' This practice enables an illustrator to keep on top of design and opens up new aspects. It can also encourage an illustrator to work in a number of ways which doubles the chance of a commission. I am not saying this is the way forward but it enables you two see things from a different point of view and develops your practice and ideas which are the ((potential)) to your illustrations. I have received lists of factors, do's and don't for this question. Not handing in an image late and always finding new ways of promotion and also listening to criticism and not always regarding it as a downfall when you go to show your portfolio.

After visiting London and making arrangements to show my portfolio around and gather opinions, I feel confident upon making such arrangements in the future and it has developed my knowledge of what to do next. An ex-graduate who I have been contacting in relation to my work and the industry was lucky enough to have an internship with Big Orange studios in London. She now works as a full time designer and illustrator. I was told by one of Cheryl Taylors colleagues that one of the reasons she has become an established illustrator is due to the contacts she was able to make when she was on the internship. I have recently been told that I have been chosen for the same internship at Big Orange studios. My plan of action is to gather as many contacts as possible whilst I'm in London and to develop my practice in terms of market research of the illustration industry and seek advice from the established illustrators I will be working with. If I had not have got this chance, which I believe to be one of the big stepping stones for an illustrator, I would prepare self promotion, mail shots, postcards and always be updating my website. At every chance, I would go and show my portfolio around agencys and be prepared to develop produce more work every chance I get.

Andy Pavitt - Tracy Kendall - COMPARE AND CONTrAST

Andy Pavitt &Tracy Kendall

Within this report I am going to compare and contrast processes of Andy Pavitt and Tracy Kendall, to what extent they are defined by the external rigours of the market place and the industry they operate in, using information From lectures at Stockport college and discussions I have had between myself and these practitioners. I aim to talk over how these illustrators relate to me, and how I can utilise information I have gathered, applying to my own practice.

Andy Pavitt, works at the Big Orange studio in London, which has been running for 15 years. He initally came to Stockport to give us a talk about his work. I first came across Pavitt's work a little into my first year on the degree, he has always inspired me with his strict use of shape, even more so, now. Pavitts vector based illustrations, are crisp and clean, flat coloured shapes without so much use of texture. Oppositly different in practice to the work of Tracy Kendall who creates her her intensified wallpapers using blown up photographic imagery. Yet, I it is more the process that ultimately separates the two illustrators.

The Industry - Time

Within the art industry, 'time' is an element that always comes to haunt any designer. The difference is, with these two practitioners, due to the way they work, and who they work for, depends on the timescale they are assigned. Pavitt has been commissioned by a range of newspapers, more specifically, the guardian, (to note but one). Because a newspaper needs new illustrations everyday, that becomes the largest amount of time you will have to complete an illustration, effectively, they have to be simple, original and communicate to their full potential. Kendall has a little more slack when it comes to time. She relies a lot on editorial articles to promote herself, and to some extent is waiting on commissioners coming to her from their discovery of these articles. Her experiment in process and practice lets her work speak out for itself. In contrast to pavitts, I think the scale of Kendalls work, the innovative ‘look’ of it and how it creates a new world, differs from Pavitts editorial pieces. The general scale of one of Kendalls sheets of wallpaper is created to fit a 2.5m tall space. I love the way kendall has designed her wallpapers, in the sense that it is almost interior design due to the space they offer but yet dominate with the large image a strong design concept which interacts with everything else in the room. Like illustration, as a field of design, it can go of on many tangents of graphics and animation. These two designers both know their limitations and stick to what they are good at, but oppositly Kendall's work seems to open more doors with fields of illustration, textile and interior design. You can see this with her creation of furniture elements for example.

The Industry - Time

Within the art industry, 'time' is an element that always comes to haunt any designer. The difference is, with these two practitioners, due to the way they work, and who they work for, depends on the timescale they are assigned. Pavitt has been commissioned by a range of newspapers, more specifically, the guardian, (to note but one). Because a newspaper needs new illustrations everyday, that becomes the largest amount of time you will have to complete an illustration, effectively, they have to be simple, original and communicate to their full potential. Kendall has a little more slack when it comes to time. She relies a lot on editorial articles to promote herself, and to some extent is waiting on commissioners coming to her from their discovery of these articles. Her experiment in process and practice lets her work speak out for itself. In contrast to pavitts, I think the scale of Kendalls work, the innovative ‘look’ of it and how it creates a new world, differs from Pavitts editorial pieces. The general scale of one of Kendalls sheets of wallpaper is created to fit a 2.5m tall space. I love the way kendall has designed her wallpapers, in the sense that it is almost interior design due to the space they offer but yet dominate with the large image a strong design concept which interacts with everything else in the room. Like illustration, as a field of design, it can go of on many tangents of graphics and animation. These two designers both know their limitations and stick to what they are good at, but oppositly Kendall's work seems to open more doors with fields of illustration, textile and interior design. You can see this with her creation of furniture elements for example.

As kendalls wallpaper designs communicate very differently to pavitts editorial work, her designs are better interpreted by aesthetic. The image makes a space pleasing to be in, it captures the viewer, whereas Pavitt’s is heavily relieant on communication. The illustration has to capture the viewer but ultimately lend itself to the text.

The Market

Within the market, the way these practitioners lend themselves to design, is again different. As kendall is more a textile artist, there is not so much a fast or tight time scale for Kendall whereas Pavitt must have had to make often trips to agencys to make contacts and gain commissions. And of course, between the two, the income also differs, kendall told us, a piece of lae she bought from a flee market for maybe £1 has earnt her £50,000- in ration to Pavitt, the cost for a single illustration would be maybe a £100-£200 but he has the cost for his studio rent, yet an advantage of working within this field and having commissions such as Pavitts with newpapers, magazines etc- is the promotion! It's a way to get yourself seen and heard about. Kendall usually promotes herself within exhibitions and as I mentioned relies upon articles which have been wrote about herself and her work. It seems somewhat disheartning for me, knowing that she is doing something she enjoys, creating these wallpapers with objects of her own desire and people approach her when they want the same for themeselves. Pavitt however, is assigned a brief and has to please the client. At the end of the day, it is the client that is commissioning you, you dont have as much freedom as a designer like Kendall. Yet you could typically class her wallpaper designs as illustrations? Why should there be such a big difference in income? Ultimatly the money you earn from an illustration is enough to pay for rent, but you have to have a job on the side. Is this why so many ex-graduating illustrators do not go progress on in the industry?

Because of the areas these two designers separate themselves, interaction of work, differs between the two. Usually because of the scale and context. Yet Kendall doesn't spend months designing, she often designs with the production techniques in mind. Which differs again from Pavitt, as all of his work is computer generated. Kendall has handcrafted her fabricated button chairs and printed her wallpapers.

Working Alone or in a studio?

Kendall works alone, Pavitt works alone, but.. is able to bounce ideas of his colleagues at big orange. The studio itself has a given itself good name within the industry because of the people within it, presently around 8. ultimately if you hand a job in late, the message will get passed on and nobody will want you working for them. Effectively, because of this enviroment, you can learn of other people and be inspired by them. Kendall, uses the market place itself to be inspired where she gathers most of the found imagery she uses within her work. I would say a big plus to the way pavitt promotes himself, is the way he gains his contacts. Cherly Taylor, who is an exgraduate went on an internship to work at big orange for a week or so, after working there, she moved down to london to work full time and is now an established illustrator. Illustrators dont always share contacts but because the market for illustrations is so wide, yet so minimal at present because there are not nearly enough jobs for a graduating illustrators, it is a lot easier to promote yourself and make make contacts. Its easy enough to get out there and get your portfolio seen. The idea of working in a studio, with others, exchanging thoughts on work, intrigues and excites me, it is something I would love to do upon leaving. In comparison to pavitt, kendall prefers to work alone because of the process of her work, the time and space she needs is inevitably enough to get in someone elses way. But, she again, is handcrafting her work and does not have an individual space in a studio to work commitedly on a computer.

Concepts

Both practitioners explore their concepts separatly, pavitt will create a range of shapes, layering them on a computer, but also creating a lot of roughs. Roughs are excessively important! As I am learning! For kendall it becomes a case of collection. To find the right spoon, or the right fork but ultimatly the idea is there instantly for her, as she works initially for herself, it is then that people approach her. Conclusively Kendalls commercial work is also her personal work, but then so is any other illustrators, but it differs somewhat.. as an illustrator is pleasing an audience and instinctivly, the client. Yet you have to enjoy illustration to be able to produce it, and especially work you are happy with. Speaking to Pavitt, we talked of how a few members within his studio are constantly creating illustrations, but they differ somewhat from commercial work, ultimatly bring out a new person, this is refreshing. Both of these practitioners have a style which is flowing through their work and is always visible. I have only just found a method of practice, but it seems very laborious, and is a contrast between these two practitiors. A mix of hand crefted elements and computer generated imagery yet, the computer side is somewhat more visible. Like Pavitt, shape offers my work a sense of structure and I am lost within it. I tend to overcomplicate, unlike kendall who uses in her most subjective work either one or two objects. Simplicity and communication I am told is the key to illustration as I have been told.

I chose these two practitioners because of their differences particularly in process which I thought could have a relevant impact upon myself as it is something I love exploring. yet if I have learnt anything from the two, it would consist of a mix of not overcomplicating and keeping things simple, to always be on the lookout for new and exiting ways of creating a design, to keep self promotion at the top of my list and to make sure that I enjoy what I'm doing, not always just trying to please the client.

Tracy Kendall

Tracy kendall graduated with an Ma from the royal college of art. She was able to show us a range of her work from screen printing to fabric and wall decoration and is now working in London on new wallpapers and decorations.

I particularly liked Kendall’s wallpapers and her innovative designs, especially the scale of them. She took shots of the wallpaper displayed in a room, you could almost imagine yourself walking through a field as if you were but a few inches tall. She has worked in many organic forms such as feathers, leaves, feathers, sequins and jigsaw puzzles.

Some of kendalls designs are based on a straight geometric dotted pattern others, random. She does like to stick to wall coverings, but has in the past made chairs and lampshades, for clients, competitions and charity. You can tell Kendall is inspired by her surroundings, using forks, knifes and spoons as primary elements of her wallpapers. When she has produced this some of her other work, such as chairs and lampshades, she has unusually attached elements when she has been making with a clothes-tagging gun, this adds to the aesthetic. Tracey likes to cut out the middle-man or has to a couple of times when her suppliers have gone bust or closed down, she actively find the source of the product and problem solved.

The motivation behind her work obviously breaks the boundaries of her inspirational designs. She has even gone against fire regulations when creating some of her work.

The question was raised about the appropriateness and the restrictions of some of the material she uses, she answered by telling us that she doesn't see it as a problem as she just makes it and its not up to her who buys it or what people do with it.

The production of her wallpapers is initially quite cheap when it comes to the designs, she expressed to us a story of how she bought a couple of pieces of lace from a flee market and then used these as a design blown up on her wallpaper. She told us that the piece of lace has earnt her around £50,000. Obviously you have to extract the costs of the making of the wallpapers and such, and she is still left with an exempt amount of money!! She also spoke of her luck and being in the right place at the right time. She now stocks her work at John Lewis.

She has participated in other different exhibitions, where she hung Christmas tress from the ceiling, the concept of walking through this atmospheric forest, the smell, emphasising the work going on in and behind the trees. This contrasting representation offered an exciting perspective and took you there to the exhibition from glancing at an image. It was beautiful. The display separated the designers in a good way as opposed to being hung in a large plain room, to some extent it encouraged you to be enveloped into the work and spend more time browsing, the work seemed somewhat lost within the surroundings, and encourages you to find it. It made it an intimate and memorable experience.

Tracey relies a lot on editorial exposure for her promotion, but also has a website that is used to sell and promote her work further.

She has traveled around the world to trade shows and for her research. She has been lucky with her practice and her willingness has brought her up to date with technology and the industry as it stands. Her work is original and fresh, and captures a new meaning and fulfillment to wallpaper design.

Thursday, 7 May 2009

A career..

| Career Opportunities |

| Written by Lawrence Zeegen | |

| Tuesday, 01 August 2000 Once upon a time an Illustration final year student could sit by their work at a degree show and wait for the offers of work to roll in. Times change and so do the methods that graduates employ to seek out work opportunities. During July my BA [Hons] Graphic Design students from the University of Brighton were kicked out of New Designers Part 2 at The Business Design Centre! Why? For daring to challenge the blandness of the exhibition and creating an installation that was both creative and thought-provoking. A large cardboard box was placed in the middle of the floor area of our designated space from out of which poked a very attractive 1970s Radio-Rental wood-effect TV monitor. A looped video of the students enjoying their own private view two weeks earlier at the college played whilst a second box contained invitations to another private view at The Truman Brewery of their "real" work just across town in Brick Lane. The students used the opportunity at New Designers to create some interest and stir some emotions. New Designers did not see the funny point and we were asked to leave for being "too creative"! Recently another creative opportunity was snatched by Illustrator, Marion Deuchars. After making a number of trips to Havana, Cuba and having produced lots of drawings, sketch books and photographs Deuchars decided that they deserved a wider viewing. Understanding a potential audience is a key factor in creating an opportunity and so she approached The Independent on Saturday Magazine’s Art Director, Gary Cochran. Rather than do what most would be content with, Deuchars cheekily mocked up the cover of the magazine with her Cuban images and created a number of spreads that utilised her work as well as her own text. The result; an issue in print within weeks that looked like the magazine had commissioned Marion Deuchars to write and produce images especially for them but also looked not unlike the original dummy she had created as the catalyst. If you look carefully at the credits for some recent editorial illustration featured in various colour supplements the name of the artist begins with www. and ends .com - another opportunity recognised and acted upon. Why just be content with showing the work commissioned on the page? These artists are leading potential customers to their on-line portfolios and picking up more work based on the extra insight to their creative world that this new opportunity promotes. What can we learn, what can we piece together from these examples of "Creatives" harnessing creative opportunities? As educators, we have a duty to encourage students to actively seek chances to create opportunities. Students must be taught to be more proactive, take more risks and recognise the potential in an idea. Getting ejected from an exhibition for being "too creative" is far more beneficial than sitting passively next to one’s work in the vain hope that the right job will just come along! Lawrence Zeegen Course Leader BA [Hons] Graphic Design BA [Hons] IllustrationUniversity of Brighton July 2000 | |

illustration degree??

| Why do an Illustration Degree? |

| Written by Jane Stanton | |

| Tuesday, 01 August 2000 It’s cropped up at all the AOI events recently. How can so many illustration courses be allowed to spring up across the country? What’s the point of us training hundreds more would-be illustrators? Do we need them? We’re flooding the industry aren’t we? As Head of Illustration on just such a course I ducked and exchanged guilty glances with a colleague from another new university during the "Is There a Future for Illustration" event and then began to wonder why some professional illustrators and educators seem so hostile to new courses in illustration. I find it rather sad and symptomatic of the lack of regard and importance that we illustrators attach to our art, that there seem to be some people in the business who cannot imagine the value to students of studying illustration without the intention of earning their living exclusively and directly from it. I’m surprised that more are not flattered that what they do has stimulated so much interest and enthusiasm to inspire others to spend three years practising and studying the subject. The recent boom in animation and digital imagery of all kinds, the enormously high standard in British children’s book illustration and the high profile of comic books, all make for a whole new generation of students well clued up on what illustration actually is. And they’re keen to find out about it and have a go themselves. Like it or not there are more students now in higher education than ever before and they want the freedom to choose what and where to study. In my day as an aspiring illustration student you had the choice of Brighton, Chelsea, Kingston, Middlesex and Norwich. Perhaps there was an option in Liverpool or Manchester? To me as a North Midlander the geography said it all, it was exclusive, something for the soft, civilised south. Now, there are thousands more people across the country being given the chance (many of them later in life) to get a higher education. On a degree course they are provided with an education not a training, they are encouraged to question and to reflect on their work and the subject. A significant proportion of them have no intention of pursuing a freelance career. Surprisingly there are extraordinarily ill informed views within the illustration and design world about what contemporary higher education is about. Gone are the days when we provided students with a desk, an angle poise lamp, a bit of advice and a project once a month. The good ones did well, the others sank without trace with little gained from their experience. There’s a lot more to it now. Most institutions these days plan with regard to regional demand as well as the educational and vocational value to students of all ages. Courses or "programmes" come and go, are absorbed, restructured on a regular basis, part-time routes are available, mature students are encouraged, feedback is sought from students and.., the big difference, they pay. Students have specific needs and expectations, they want the whole university experience. Mostly they are practical, realistic, they and their parents want to know how an illustration degree can be useful to them in the world outside. They can identify this because in addition to the obvious craft and skills based activities such as drawing, painting and IT, we are able to teach them about: problem solving, innovation, original thinking, collaboration, communication, developing a personal agenda, research, understanding text, project management, understanding audiences, historical and social issues, critical analysis, contextual and theoretical awareness. They learn that these are valuable experience and skills to have in any creative business. The whole illustration industry needs to get in on this new approach to higher education and latch on to the new opportunities that it provides illustration because, as most of us are aware, something that goes with many of these new courses is a commitment to research and practice. Although initially slow off the mark, art and design courses have now. begun to exploit the research funding mechanisms available in higher education and this can do nothing but good, enriching both our identity and the source of material on British illustration as a subject and as a profession. There’s plenty of opportunity here for collaboration on exhibitions, conferences, fellowships, publications and the like. Anyone would agree who has seen Wendy Coates-Smith and Martin Salisbury’s excellent journal "Line" from Anglia Polytechnic University recently (with absorbing articles on Ronald Searle, Sue Coe, Edward Bawden and Walter Hoyle) and Robert Mason’s publication on illustration in the 1990’s "A Digital Dolly" published by Norwich School of Art and Design. We couldn’t do better than follow the example of this country’s currently best known and best loved illustrator, Quentin Blake who, whilst he was teaching at the The Royal College of Art, went a long way towards lending gravitas and authority to the art of illustration by organising publications, workshops and exhibitions such as "25 Years of Illustration at the RCA", "The Artist as Reporter" and "Radical Illustration". Since then he has also been responsible in his role as children’s laureate, and through the media, for promoting and stimulating interest in illustration. If only there was more of this genuine and contributing interest in education at all levels from individuals in the professional world of illustration and I have to say, the design world, perhaps there might be the substantial national archive and gallery that there ought to be. We need to get together on these sorts of initiatives rather than see ourselves as competitors or rivals and then the sky’s the limit. There’s a new wave of interest in illustration, it’s a rich and fascinating part of British visual culture, it extends beyond the boundaries of a job of work, so let’s have a genuine partnership and co-operation between the illustrators and the educators (after all many of us are involved in both) Let’s capitalise on this enthusiasm and opportunity, raise the profile and deepen the wealth of material on the art that we and our students are so passionate about. Jane Stanton is head of Illustration at the University of Derby and a practising illustrator and artist | |

students to proffessionals

| And then they left - From Students to Professionals |

| Written by Mario Minichiello | |

| Sunday, 01 December 2002 Before I begin apologies to all ex-students NOT included in this report. It represents just a small cross section of graduates from the past ten years to whom I put the questions:

"At art school I learnt to draw. The most important aspects were establishing my visual language, learning the business side of the profession and acquiring the drive and discipline to succeed. My work is decorative and colourful and predominantly figurative and I have worked in just about every field since leaving. I think that clients expect a really high standard and that the quantity of work is not always reflected in the fee. Next I would like to learn Flash 5 animation and work for web design agencies." MATT ROCK left in 2001 was featured as Guardian graduate for that year. "The most important things I did at art school were: develop my painting ability, try other media such as print and digital photography, become more open-minded and improve my time management and organisational skills. Finishing my first commission was of most value. It gave me a real boost. My work is based on well-observed drawing, communicated mostly through computer 2D animation. I need clear briefing and my own strong opinion on the topic to be reflected. I have experienced problems with over picky clients asking me to alter minor things, and problems with computer platforms compatibility. I would like next - a crash proof computer." MARSHA WHITE: 2000 "I always wanted to be an illustrator but went to art college with a fairly vague idea of what that entailed. Once there, my perspective was widened a lot but my personal aim was strengthened rather than altered. The course provided the chance to develop my own language and test ideas. Also it forced us to be critical, both of our own work and other people's. The professionalism and high standards that were expected were very helpful things to take away! What do I value most from the past five years? Firstly my degree, and then the commissions I have had, mainly my children's book because I wrote it too and feel I was part of the process of it being published. Also working for Persil because it is such a high profile company. I am also pleased to be still going! I would describe my work as fun: bright, light-hearted, with a sense of humour, animal-obsessed, personal and vibrant. I take inspiration from other people's work, fashion, colours, animals, especially dogs and specifically whippets, music, interesting-looking people and humour, and cups of tea. I would like to continue to work in children's books and for an advertising agency. I like to think I am quite flexible and would love to be commissioned for a magazine. It does seem that because I have done a lot of dogs it is what I am most frequently asked to do. I believe that I work most creatively under pressure. Since leaving college I haven't been in a studio situation but found that very productive at college. I find getting constant well-paid work the hardest thing! Perhaps I need an agent. I promote myself through Contact. For two years that has been my main method. Keeping in touch with people that showed even the slightest glimmer of interest has helped. Other than that, sending out samples, being on the cottonwolf and Katch-up websites and planning my own and of course, going to meet clients with my A3 portfolio and a smile. I don't have a long-term game plan, just to see where illustration might take me. Since I have left the path has been more up and down than I could have expected! As to what changes would I like to see in the business? I don't feel especially well qualified to answer but I think better fees would be a start. Also technicalities with rights and licences sometimes seem a bit tricky and weighted in the clients' favour." RICHARD JOHNSON left in1999 and was awarded a Silver Medal in Images 26 "My ambition and hunger to become a successful illustrator just got bigger and bigger the more I learnt. It was a constant battle to find my visual language, but I got great advice. Learning the actual process of answering a brief, the decision making that goes into producing an illustration that works - was vital. I use my sketchbooks for reference and I'd say my style is fairly traditional, relying heavily on drawing and colour. My best moments so far have been: my first proper commission, my first Children's Picture Book and recently being awarded the Silver Medal in Images But in the last few weeks, things have exploded! I've got 8 jobs on the go and I don't know whether to laugh or cry. CYRUS DEBOO - Left art school in 1990. Established professional. "I wanted to be a famous graphic designer. Two thirds into my Graphic Design course, I went on a week's placement and reality rained down on me. I found the work very dull and tedious. So at the last minute I changed to illustration. I came out of my shell, had time and space to experiment, make mistakes, looked and absorbed. I was inspired by visiting practitioners, like Matthew Richardson. I use a digital line and flat colour. Nowadays I do spend more time perfecting the idea, and believe it makes my work more creditable. I'd love to have clear and realistically time-scaled briefs and I hate commissioners who are indecisive. It stifles creativity. I hate being asked to sell all rights for the job for a poultry fee and I'd like to see a law introduced to fine companies who withhold payment after 30 days of receiving an invoice. I occasionally find it awkward to fix a price and would welcome a generally accepted scale of fees for specific jobs. Good news is that the Internet and email brings the world to your screen, makes working for clients in different countries possible from my desk in London. Three cheers for WWW Dot." FRAZER HUDSON left in 1990. He is an established professional who has long been involved with the AOI. "At art school I started by wanting to draw realistically, but progressed to using drawing more sparsely to communicate the main thing - the idea. I would describe my work as 'conscious'. My best achievements have been choosing to work a 3-day week and understanding the relationship between work, money and freedom. I hate an ill-thought-out brief and Monday mornings. I'd like to design political or issue-lead posters like Abram Games and I'd love to swap roles, commissioning other illustrators who I admire, working within advertising. Periods of illness have also given me some thought-provoking insights into what makes me tick. I would like to always be in the right place at the right time. I would like to see a major annual competition, which forms the basis for highlighting the power of illustration, as a competitor to The Turner Prize." Many thanks to all who took part. | |

photo- technology

| Photo-Technology |

| Written by Lisa Kopper | |

| Friday, 01 June 2001 Will the real drawings please stand up. Photo-technology. Lisa Kopper explains how it is done As a professional illustrator, I have noticed changes taking place over the years which suggest an underlying shift of attitude amongst those who illustrate and those who commission illustration. The photograph as a foundation to illustration has become more and more prevalent. Is this 'cheating'? Or, if the end result works, does reliance on photography matter? I think it does. Photo-techniques used to be confined to advertising. Perhaps even then, some clever book illustrators were using them, but they did not really come into children's picture book publishing in a big way until the early eighties when the need for books which reflected our multicultural society became an issue. Publishers under pressure to produce such books found it difficult to find artists who could draw Black people. There were few Black illustrators (as is still the case today). Cartoon imagery was out as publishers feared they would be criticised for racial stereotyping if the representation of Black people was not realistic. Innovative writers and photographers like Joan Solomon partially solved the problem by doing straight photographic books about children from different cultures. These books filled a gap but tended to be information books. This was not appropriate for the majority of picture books and other solutions had to be found. Some picture book artists turned to photographs and began to produce super-realistic drawn images directly from them : photo-realism. No one could say that their Black people did not look like Black people - they were so good, they looked just like photographs. In my view this was cheating in a profound sense because the real issue of why it is so difficult for people of one culture to draw people from another, was not addressed. I do not blame the artists for this; they were responding to a demand in the best way they knew how. But, over time, what has emerged from this trend is a kind of visual apartheid. Today, I would hazard a guess that 85% of children's books depicting Black people use photo-technology of some kind in their image creation. But just as the photo techniques did not stay confined to advertising neither did they stay confined to children's multicultural illustration. The steady march of 'photo-drawing' gradually reached every corner of illustration. It is easy to see why. On the surface of things, photography is a short cut to something very difficult to achieve : good drawing. But there is a price for pursuing the icing rather than the cake, form before content, and that price is the potential loss of a skill which is the foundation of visual imagination. The frightening thing is that it is happening by stealth. There has not, so far as I know, been any serious discussion of how photo technologies are affecting not just children's book imagery, but the very nature of drawing itself - how this skill is taught and nurtured. Arguably, drawing is one of the purest forms of visual expression - the shortest route between the eye and the paper. To be able to draw freely means to give form not only to what we see around us, but also to what we cannot see - the depiction of the imaginary. By its very nature, the photograph is bound to what already exists. In my view, the most excruciating examples of photo illustration are when the artist does attempt fantasy and cobbles together incongruous, photo-derived images such as a girl sitting on a flying tiger or such like, with structural conventions such as viewpoint, perspective and harmonious detailing thrown to the winds. The best photo-illustrators often spend much of their time and money setting-up their photos. This can mean dressing and posing models, lighting, travelling to the locations, and sometimes expensive equipment to ensure quality transference of their photos onto canvas, paper or computer disk. Many photo-illustrators are talented photographers and do an excellent job - but why bother to make a drawing of a photograph? Has it become so important to be 'real' because we are losing the skills which gave us the freedom to be unreal? And what makes people think that a photo is so real anyway? Eye to hand drawing is a means of communication, 'acting on paper', as I often tell school children. It is often the flaws that give a drawing life, movement and character. Sometimes accidental perspective or detail also emphasises the spirit as well as the form of the subject. A photograph is an instantaneous, two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional object. As the camera only has one 'eye', it already sees the world in a very different way from us. Make a drawing from this photograph, and we move yet another step away from the life and dynamics of the original subject. Thus many 'photo drawings' are curiously static and dead, their subjects frozen in an instant rather than expressing their true nature. It is a process which often cuts the heart and life out of an image. ... Photography is a simple mechanical activity and drawing requires a profound understanding of form and character. This trend is reinforced by the number of prestigious prizes awarded to photo-derived books. Perhaps those who award such prizes know little of the techniques involved? However, the message this sends to young artists is clear: learning how to draw does not matter. This is not a good message even if some people prefer the style of photo-illustration to free drawn images. Certainly illustrators who can draw use photographs much more creatively and successfully than those who cannot and it is immediately obvious to an educated eye which is which. Some artists use limited photo-aids very imaginatively. Understanding techniques I believe it is important to understand the difference between something that has been created by the skill and imagination of the artist or as a piece of photographic sleight of hand. Perhaps to help with visual awareness, photo-illustration should be described as such on book jackets. Over the last 150 years the photograph has often been seen as the benchmark of reality, but before (and after) photography arrived on the scene, artists were creating their own realities through the sheer skill of their observation and mechanical ability. The realities of Rackham and Shepard transcend the mere representational. They glow with character and the inner qualities of that which they represent. Even if our drawing abilities are less breathtaking we should, I believe, still have the same ultimate objective. We must carefully guard and preserve the skill of drawing for the future, or we risk losing its value for ever. Lisa Kopper has been an illustrator working in the children's book industry for over 18 years. She is best known for her multicultural work (eg Jafta: The Homecoming, Puffin, 0 14 054467 4, £4.99) and her Daisy books (eg Daisy Thinks She is a Baby, Puffin, 0 14 054826 2, £4.99). As she says, 'No photos used. Honest! A version article was originally published in "books for keeps" | |

Design Observer

Having a browse on the design observer website, I came across this article, I thought it was interesting upon the fact that it discusses a fair few issues within the industry presently. How Illustration has somehow disappeared or been taken over by photography and the contrast between illustration and graphic design

Graphic Design vs. Illustration

The professional world of illustration is widely believed to be in poor shape. As Steven Heller noted recently: "I am an advocate of illustration and saddened by its loss of stature among editors who feel photography is somehow more effective (and controllable)." There are, of course, many reasons for illustration's fading stature other than the commercial world's hard-nosed preference for photography over the arty vagueness of hand-rendered imagery. The ubiquity of software that allows graphic designers to generate their own imagery is another factor, as is the rise of illustration stock libraries. Yet perhaps illustration's current status owes most to its near-total eclipse by graphic design. To understand the contemporary state of illustration, we need to look at its relationship with graphic design.

There was a time when graphic design and illustration were indivisible. Many of the great designers of the 20th century were also illustrators and moved effortlessly between image-making and typographic functionalism. Traditionally, most designers viewed illustration with reverence; many even regarded it as inherently superior to design. And with good reason: design was about the anonymous conveying of messages, while illustration was frequently about vivid displays of personal authorship. Like artists, illustrators signed their work, and some were even public figures (no graphic designer ever enjoyed the fame of Norman Rockwell, for example). As Ed Fella, a practitioner with feet in both camps, sagely noted: "Whereas graphic design is more anonymous, all illustration is sold for its particular and individual style."

But during the 1990s, illustration's "individual style" became a liability. Visual communication was colonized by tough-minded, business-driven graphic designers who gave their clients what they wanted: branding, strategy and the precision-tooled delivery of commercial messages. Even amongst more idealistic designers — designers who embraced theory, political activism (no big-name illustrators signed the First Things First manifesto), and notions of self-authorship — it became apparent that highly expressive graphic design could achieve some of the conceptual and aesthetic impact of illustration. The outcome of all this was that designers seemed to lose the habit of commissioning illustration, and most illustration was relegated to mere decoration.

Buy why?

It's a much-touted nostrum that we live in a visual world. Sure, the media landscape is saturated with images, but these images are nearly always accompanied by words signposting us to some sort of financial transaction. Graphic design's eclipsing of illustration is explained by illustration's lack of verbal explicitness. Graphic design is almost exclusively about precise communication, and its facility to combine words and images makes it a far more potent force than illustration. Milton Glaser has said: "In a culture that values commerce above all other things, the imaginative potential of illustration has become irrelevant... Illustration is now too idiosyncratic."

I was made aware of the main reason for graphic design's supremacy in the commercial world from an unlikely source. In his book What Good Are the Arts, the English academic John Carey sets out to discover an absolute measure for artistic worth. Dealing with the visual arts, Carey concludes that there is no defining yardstick: anything we choose to call art, is art. It's really a matter of personal choice. But halfway through his book Carey puts the case for literature. He sets out "to show why literature is superior to the other arts and can do things they cannot do."

For Carey, literature is the pre-eminent art form: "unlike the other arts," he writes, "it can criticize itself. Pieces of music can parody other pieces, and paintings can caricature paintings. But this does not amount to a total rejection of music and painting. Literature, however, can totally reject literature, and in this it shows itself more powerful and self-aware than any other art."

The attributes Carey applies to literature also apply to commercial communications. Words rule. Explicit language coupled with explicit images (devoid of ambiguity and nuance) is the lingua franca of advertising and marketing. We seem to have reached a point in Western culture where the abstract is no longer tenable. We demand explicitness in everything, which perhaps explains the contemporary appetite for endless news, reality television, the depiction of graphic violence and hardcore pornography.

Graphic design's ability to deliver explicit messages makes it a major (if little recognized) force in the modern world: it is embedded in the commercial infrastructure. Illustration, on the other hand, with its woolly ambiguity and its allusive ability to convey feeling and emotion, makes it too dangerous to be allowed to enter the corporate bloodstream. Our visual lives are the poorer for this.

Illustration Mundo

Upon searching for issues presently affecting the design industry, I stumbled across this..

What changes in the illustration industry have you seen in the last 10 - 15 years? What are some recent trends?

- I feel that there was a swing toward photography for a while there but in the last few years I've seen that illustration is getting more visibility and credit, and with greater success and return for clients.

- There are substantially more illustrators now than there ever were before. This may in part be due to the 'manipulated photography' as illustration trend and the 'graphic design work' as illustration trend, but I believe it is also attributable to what appears to be an expansion of illustration, animation and even comic book art programs in many art schools around the world. There is a lot more competition for illustrators out there now.

- The art directors, creative directors, designers and art buyers that have jobs are under greater pressure to perform at higher levels than historically expected and with less resources and support staff.

- Illustrators started selling stock artwork to and through large stock agencies for low prices. The illustrators that I hear complaining about stock are primarily the illustrators that sold their work as stock. My advice - don't do it and you'll never be sorry you did.

- Stylistic trends: Very clean, slick and slightly stiff digital illustration has been popular for a while now, as is a style that I would describe as looking like 'information graphics', but clients are starting to get bored with this. I don't want to scare artists that just render color digitally - that's not what I'm talking about. I often hear the words 'authentic', 'painted' and 'hand-made' coming up lately. Graphic novels are a trend, as is the concept of the illustrator as a writer as well - but beware, just because you can write does not mean that you should. Be self-scrutinizing and if that fails have someone else scrutinize the writing. Bad writing will bring down good illustration. Lastly there has been a flood of illustrators that generate their work from photographic imagery and manipulate it slightly in a few different ways to create an illustration. This is a trend that has been jumped on by artists at an alarming rate (it is by far the largest number of representation inquiries we receive)

Wednesday, 6 May 2009

Rick Poyner quizes Dan Fern - THE RCA's head of communication design reflects on the future of post-graduate design studies

‘A lot of illustration sits very awkwardly alongside the contemporary digital typography scene. It can look naive, almost folksy’

Dan Fern was born in Eastbourne, England in 1945. He studied for diploma in graphic design from 1964-67, then took an MA in illustration at the Royal College of Art, graduating in 1970. From 1970-73, he lived and worked in Amsterdam, where he encountered work by Zwart, Werkman and the De Stijl typographers that was to have a lasting influence on his own aesthetic concerns. Returning to London, he began a freelance career as an illustrator for Nova, The Sunday Times Magazine and other publications. In 1974, he was invited to teach in the illustration department at the RCA and his increasing involvement led, in 1986, to his appointment as full-time professor of illustration. IN 1994, the RCA was restructured into eight schools and Fern became head of the School of Communication Design, with responsibility for graphic design, illustration and interactive multimedia. IN parallel with his educational commitments, he has continued to work as a freelance illustrator and image-maker in a variety of contexts. His clients include many British design groups and the advertising agencies Doyle Dane Bernach, J. Walter Thompson and Young & Rubicam. Publishing and music business clients include Penguin, Faber & Faber, A&M Virgin, Decca, Building, New Scientist, design and Radio Times. He has exhibited in many one-man shows and group exhibitions in Europe, the US and Japan and. in 1988, was the curator of 'Breakthrough', a retrospective exhibition of RCA illustration. Recently, he has turned to the moving image, with commissions from London's South Bank Centre and Goethe Institute to create non-narrative films to accompany live performances of works by the contemporary composers Detlev Glanert and Harrison Birtwistle.

Rick Poynor: Has there been any inclination from the Royal College of Art's incoming rector Christopher Frayling of what his policy towards the School of Communication will be?

Dan Fern: There's nothing specific yet. I've been involved for the past three or four years in a number of different areas where we've been talking about the future direction of the college. The college's first academic plan was put into operation three years ago with the formation of the schools instead of the old Faculty Boards. We're talking about part two of that plan at the moment and Chris, as chairman of the heads of schools committee, is leading those discussions.

Communication design is an area that we haven't come to specifically yet, but if we had to look for signs of what he thinks about it, and about the relationship between graphics and illustration, I suppose the fact that he was largely instrumental in appointing me two years ago to run graphic design shows that he thinks my general approach to illustration could also be applied to graphics - and thereby the whole of the School of Communication Design.

RP: What was the purpose of restructuring and forming the new schools?

DF: It was partly a way to regroup courses that have philosophical similarities and links in a professional sense, and to make them more autonomous than they have been in the past. It was part of a gradual devolution of the administrative processes out from the centre of the college and into the schools. The heads of schools have a considerable amount of control over the areas they administer - over staffing, budget allocation, research policy, proposals for the future developments and so on. Obviously, it's very much guided by parameters established elsewhere, in the Academic Standards Committee and the Academic Boards and so on.

The restructuring was a way of giving clusters of disciplines a greater sense of identity. There was a danger that we'd start to lose the collegiate sense of being part of a unique multi-disciplinary polytechnic. But that hasn't happened. It's working very well.

RP: How would you define the purpose of studying communication design at MA level?

DF: Well, I think it enables the very best people, who come to us from the undergraduate sector, to develop their talents in an experimental and, I hope, encouraging environment - to be a sort of hothouse, if you like. The school is geared towards individual progress; there isn't a set programme. The accent is on the development of an individual's talents and interests and obsessions to encourage a very strong personal aesthetic, which then hopefully carries them into which ever area of commercial or professional life they choose to follow. But to do that from a position of strength, knowing what their work is about and what their roots are and what their precedents are. So it's very much to do with developing that sort of atmosphere. But also, since we're a university, we must work within an intellectual framework as well.

That's what the situation has been and until comparatively recently it was enough. The RCA could be a goal for people in the undergraduate sector because we were literally the only place of this type. Now we're starting to have competition - nationally and internationally - and it will increase, which frees us to move on to different things altogether. At the moment we are working on part two of the academic plan, which is what the function of a place like the RCA should be over the next ten years, and how its role in the future might be different from its role in the past. All sorts of models are starting to emerge from that: I have my own ideas about it and so do other people here and we're in the process of debating all of that at the moment.

RP: What are the key differences between what the RCA aims to offer communications designers and what some of those rival institutions now offer? How would you position the college?

DF: There are some very physical things. We're the only post-graduate polytechnic of art and design, and the scope and range of work that happens within these few hundred square metres is fantastic. I know of no other place that has such a wide range of postgraduate courses or where the inter-relationship between those courses is as great as it is here.

As far as communication design itself goes, it's difficult to put a finger on exactly what makes us different from other institutions. My own feeling is that one thing characterises us is a relationship between the fine arts and the applied arts. In my own teaching and personal work, that's very important. I am as likely, in a tutorial with a graphic design student, to talk about Richard Serra or Donald Judd or Robert Racine or Barbara Kruger as I am to talk about another designer. I find the wider cultural knowledge of a lot of designers rather - so much of graphics is self-referential and inward-looking. we need to encourage designers to look beyond what other designers are doing, to film and music and the fine arts . . .